The Power of Safe Spaces

Psychological Safety is More Than a Buzzword

Building Psychological Safety: The Path to Wholeness at Work

Psychological safety has become one of those phrases that float around in conference rooms and leadership trainings, touted as the secret sauce of innovative companies. The term gets dropped into PowerPoint decks and corporate value statements, often with little clarity about what it actually means or how to create it. At its simplest, psychological safety is the belief that you can speak up, take risks, share an idea, ask a question, or even make a mistake without being punished, humiliated, or shamed. Amy Edmondson’s research at Harvard Business School made the concept famous when she showed that teams with high psychological safety consistently outperform those with low psychological safety—even when individual talent levels were similar (Edmondson 2019).

But when we reduce psychological safety to just a management tool for higher productivity, we miss its deeper invitation. True psychological safety is not simply about protecting people from punishment. It is about creating environments where people can be whole. And that is a much larger, more transformative vision than simply encouraging people to speak up during meetings.

What It Means to Be Whole

Before we can talk about building psychological safety, we need to define what we mean by whole. Wholeness is the state of living in integrity with ourselves, where the various pieces of our identity, experience, and values are not forced to compete with one another. To be whole is to live without the constant pressure to fracture ourselves into different versions for different contexts: the professional version that never gets tired, the family version that never gets impatient, the social version that never feels insecure. Wholeness means we are not living split lives, managing masks for every setting.

Wholeness is not about indiscriminate transparency or confessional oversharing. Rather, it is about integration: the capacity to bring our inner life and outer life into alignment, so that what we say, what we do, and what we value point in the same direction. Psychologist Carl Rogers called this congruence, describing it as the alignment of self-concept and lived experience (Rogers 1961). When we are congruent, we feel at home in our own skin. When we are not, we feel a constant hum of tension, as if we are playing a part rather than living a life.

From a psychological standpoint, wholeness also means welcoming the disowned or shadowed parts of ourselves back into awareness. Jungian thought holds that the path to individuation—the process of becoming fully oneself—requires acknowledging and integrating the traits we have repressed to stay acceptable to others (Jung 1959). In the workplace, this might mean recovering the part of ourselves that once dared to question authority, or the part that loved to experiment and play, or even the part that admits to limits and asks for help.

In this sense, wholeness is not a destination but a practice: the daily decision to live without cutting off parts of who we are for the sake of fitting in. It allows us to show up in a way that is honest, connected, and present, even when things are messy. Wholeness gives us access to our full range of emotional intelligence, creativity, and courage. Without it, we may be technically present at work but emotionally absent, contributing only the most cautious and surface-level parts of our thinking.

Why Wholeness Matters at Work

Many of us work in environments that ask us—sometimes subtly, sometimes bluntly—to leave parts of ourselves at the door. We may be told that “personal stuff” is not appropriate for work, or that vulnerability is a distraction from performance. Even when no one says it outright, organizational cultures often reward stoicism, agreeableness, and constant output, quietly punishing hesitation, dissent, or struggle. We learn to split off our emotions, our personal challenges, or even our creative instincts to avoid being seen as difficult or unprofessional.

But there is a cost to living fractured. When we have to monitor every word and gesture to ensure we will be accepted, our nervous system interprets that environment as unsafe. We become hypervigilant, scanning for signs of approval or rejection, constantly modulating ourselves to stay in the group’s good graces. This chronic vigilance drains cognitive resources, leaving us with less energy for creativity and collaboration (Siegel 2010). Over time, it leads to emotional exhaustion and disengagement.

Burnout is often the body’s revolt against this kind of fragmentation. When we are forced to silence or contort ourselves day after day, eventually the body refuses to cooperate. We get sick more often, lose our capacity to focus, or simply feel numb (Maslach and Leiter 2021). The way out is not simply more vacation days or a mindfulness app. It is the restoration of wholeness—the creation of environments where we no longer have to waste so much energy on self-protection.

Psychological safety is the organizational mechanism that allows this restoration to take place. When people believe they can speak honestly without retaliation, when they can share ideas without ridicule, when they can admit a mistake without fear of being cast out, they stop performing and start participating. Their nervous system relaxes, freeing up the energy that had been used for impression management. This is why teams with high psychological safety outperform others: the collective intelligence of the group becomes available because no one is hiding in self-protection mode (Edmondson 2019).

Wholeness as the Ground of Safety

When we ground psychological safety in wholeness, we move beyond seeing it as a tactic for better business outcomes and begin to see it as a profoundly human commitment. Creating safety is not about coddling employees or shielding them from challenge. It is about saying: you do not have to split yourself apart to belong here.

Imagine two organizations. In the first, a junior employee notices a flaw in the rollout plan for a product launch. She worries that speaking up will make her look incompetent or negative. She stays quiet. The flaw is discovered too late, and the company loses money and trust. In the second organization, the same employee speaks up early because she knows her voice will be taken seriously. Her team thanks her for catching the issue, and the plan is corrected. The difference between the two scenarios is not the employee’s personality; it is whether the environment allowed her to be whole—aligned enough with her values to risk saying the hard thing.

Wholeness reorients psychological safety from being about fear reduction to being about belonging. It is not just about avoiding harm but about creating the conditions for integration. This is what makes organizations truly resilient: when people are whole, they can contribute fully, disagree constructively, and recover quickly from challenges.

Building Psychological Safety: Practical Pathways

Developing psychological safety is not a one-time workshop or a well-worded company value statement. It is the patient, ongoing work of culture-shaping. Here are several practical ways organizations can begin.

1. Model Wholeness at the Top

Leaders set the emotional tone of the organization. When they share what they are learning, admit when they have made a mistake, and invite feedback on their own performance, they send a powerful signal: it is safe to be imperfect here (Brown 2018). This kind of modeling must be authentic rather than performative—employees can spot a staged vulnerability exercise from a mile away. But when leaders tell the truth about their own growth edges, they create a permission structure for everyone else to do the same.

2. Normalize Dissent and Curiosity

Organizations often pay lip service to “innovation” but quietly punish dissent, which is fatal to psychological safety. Teams flourish when disagreement is treated as a sign of engagement rather than betrayal. Practical ways to encourage this include explicitly inviting alternative viewpoints in meetings (“What are we missing?” “Who sees it differently?”) and publicly thanking those who raise difficult questions (Detert and Burris 2007). Curiosity should be rewarded, not punished, even when it complicates the path forward.

3. Create Rhythms of Reflection and Repair

Wholeness is not a one-time achievement but an ongoing practice. Teams need structured opportunities to reflect, name tensions, and repair ruptures. Retrospectives, after-action reviews, and listening sessions provide space for realignment. The key is to normalize these rhythms so that repair is part of the workflow, not just a crisis intervention when something has gone wrong (Kegan and Lahey 2016).

4. Attend to the Nervous System of the Organization

Psychological safety is experienced as much in the body as in the mind. If the pace of work is relentless, if deadlines leave no margin for rest, or if feedback is delivered in a harsh or shaming tone, employees will not feel safe no matter how many times the company says they are. Organizations can signal safety by building in breathing room, pacing projects realistically, and making space for recovery (Siegel 2010).

5. Design for Inclusivity

Wholeness cannot thrive where only a narrow range of identities or communication styles are acceptable. Inclusivity here is not only demographic diversity but also cognitive and emotional diversity. Introverts, neurodivergent employees, and those from different cultural backgrounds need avenues to contribute that do not force them to conform to a single dominant mode of expression (Roberson 2019). Multiple formats for participation—written, spoken, asynchronous—help create a broader sense of safety.

The Long Game of Wholeness

Trust, once broken, takes time to rebuild. Psychological safety is therefore a long game: it grows through hundreds of small interactions that communicate, “You belong here. You are safe here. You can be yourself here.” It is also fragile, which means it must be actively maintained. One shaming comment from a leader can undo months of careful culture-building.

But when cultivated, psychological safety creates compounding returns. People speak up sooner when problems emerge, which prevents small issues from snowballing into crises. Teams learn faster, innovate more often, and recover more quickly from setbacks. The organization becomes less brittle, more adaptive, and better able to absorb shocks.

Ultimately, psychological safety is not simply the absence of fear. It is the presence of wholeness. It is the lived reality that people can bring their full selves into the room without fear of losing belonging. Organizations that embrace this vision do more than optimize for quarterly results; they become spaces where people can practice integration, where the fractures of modern life can begin to mend. In a culture where fragmentation and burnout are so common, this might be one of the most meaningful contributions a workplace can make.

REFERENCES

Brown, Brené. Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts. New York: Random House, 2018.

Detert, James R., and Ethan R. Burris. “Leadership Behavior and Employee Voice: Is the Door Really Open?” Academy of Management Journal 50, no. 4 (2007): 869–884.

Edmondson, Amy C. The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2019.

Jung, Carl G. Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1959.

Kegan, Robert, and Lisa Laskow Lahey. An Everyone Culture: Becoming a Deliberately Developmental Organization. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2016.

Maslach, Christina, and Michael P. Leiter. The Burnout Challenge: Managing People’s Relationships with Their Jobs. Boston: Harvard University Press, 2021.

Roberson, Quinetta M. “Diversity and Inclusion in the Workplace: A Review, Synthesis, and Future Research Agenda.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 6 (2019): 69–88.

Rogers, Carl R. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

Siegel, Daniel J. The Mindful Therapist: A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration. New York: W.W. Norton, 2010.

Resource Library:

For the Scholar (Heady, academic research for those who enjoy it.)

“Psychological Safety: A Systematic Review of the Literature”

This is a systematic review that synthesizes empirical findings: what helps build psychological safety, what outcomes are linked to it, what gaps remain. Very useful.

For the Care-giver (Digging deeper into caring for people, including ourselves.)

“How HR Can Help Create Psychological Safety in the Workplace”

A more general article, but with good actionable guidance for HR and caregivers: encouraging open communication, making failure / mistakes safe, coaching leaders etc.

For Fun

“12 Psychological Safety Activities for Employees in the Workplace”

A list of free, light-hearted exercises you can use with teams: things like “Host an Anxiety Party”, “Personal Histories”, “Fail Forward”, etc. Great for injecting energy into sessions

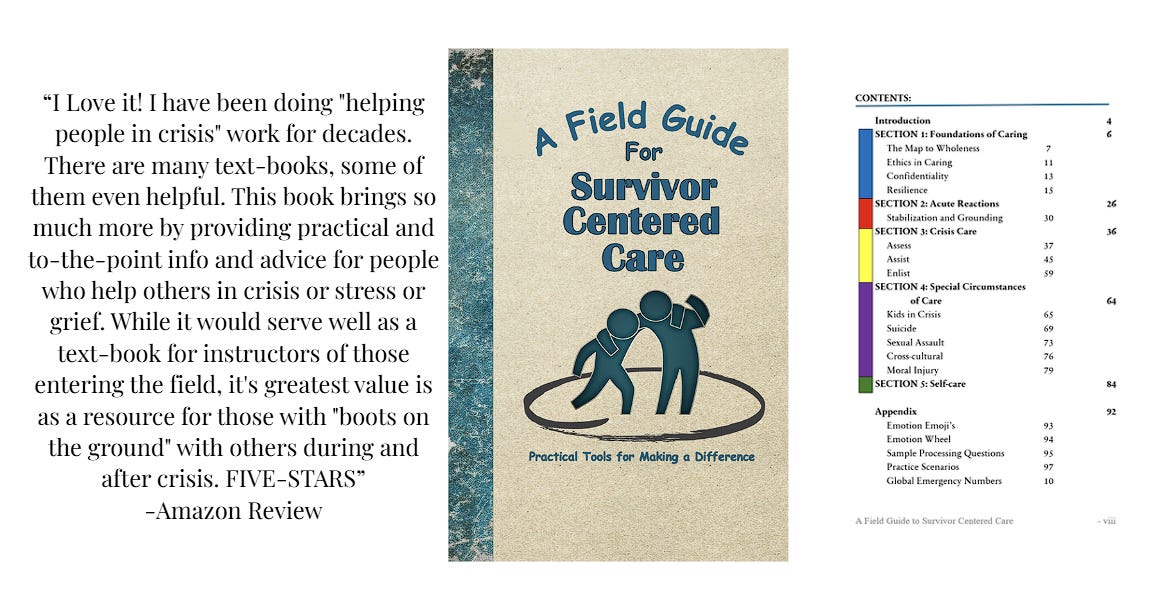

The reviews are coming in.

Here is what one reader reported: